Enhancing the Current Population Survey for policy analysis

We've used modern data science techniques to make PolicyEngine the UK's most accurate microsimulation model. In 2023, we'll do the same in the US.

Contents

Why is the CPS inaccurate?

Our plan to enhance the CPS

Why our approach will work

The

In 2023, we will enhance the CPS by integrating it with IRS tax records and reweighting it to minimize deviations from administrative aggregates. This enhanced dataset will be used in the PolicyEngine microsimulation app and will also be made available as an open resource for other policy research.

We’re grateful to Dylan Hirsch-Shell for supporting this project.

Why is the CPS inaccurate?#

The Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics run the CPS monthly. Each March, they ask deeper questions on households’ activity in the prior calendar year, in the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). We use the CPS ASEC (which we refer to as the CPS) for our policy simulations, as do many other analysts; for example, the Census Bureau uses it to produce their

-

It undercaptures benefits and tax credits, leading to underestimated impacts on certain populations. For example,

CPS respondents under-report SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits by about a third. -

It

top-codes income variables above $1 million , which can distort the income distribution and impact policy simulations. -

With only 100,000 households, the CPS can produce volatile estimates when broken down by subpopulations, especially at the state level.

-

It lacks some important information, such as assets, that can impact taxes and benefits.

-

The CPS is based on data that is 1–2 years old and is not extrapolated to predict future policy impacts.

These limitations can reduce the accuracy and usefulness of the CPS for policy simulations and other research. For example, CPS-based projections will tend to underestimate the budgetary impacts of reforming SNAP or instituting a tax on top earners, and will be unable to estimate the impacts of wealth taxes or reforms to asset limits in benefit programs.

Our plan to enhance the CPS#

To address these issues, we plan to integrate several household datasets and tune them to more closely match administrative totals. This process will involve the following steps:

-

Import the CPS and replace reported taxes and benefits with computed amounts from our microsimulation model.

-

Duplicate the CPS, remove income variables, and replace them with imputed values from

IRS tax records using our open-sourcesynthimpute software for machine learning-based quantile regression. -

Develop a loss metric based on the differences between the survey’s aggregates and true aggregates published by the government.

-

Use gradient descent to adjust the household survey weights in the duplicated CPS and minimize the loss. -

Integrate the reweighted CPS-IRS dataset with the Survey of Consumer Finances and Consumer Expenditure Survey to create a comprehensive household dataset, also with synthimpute .

-

Repeat steps 3 and 4 for each subnational area (state, congressional district, state legislative district, etc.) to produce weights for those areas.

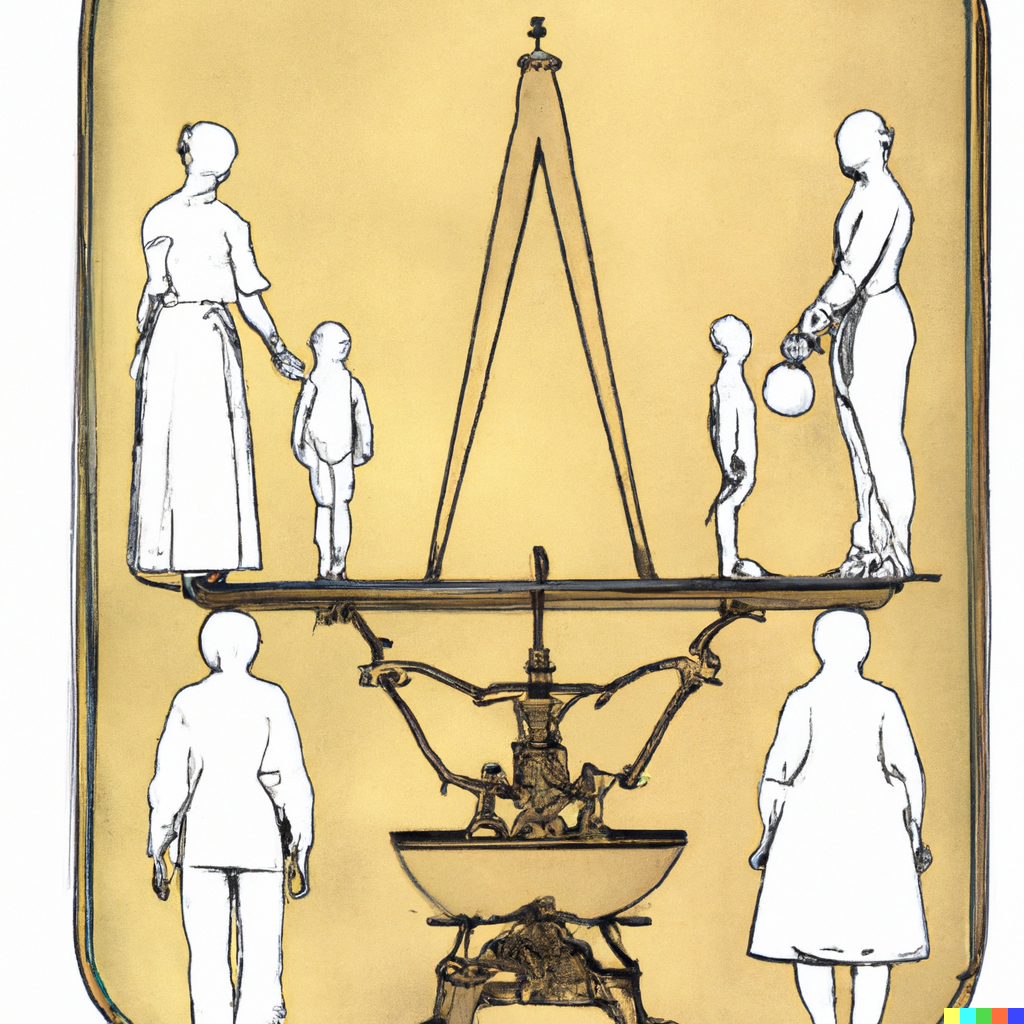

The diagram below characterizes this procedure (

We have successfully implemented steps 1–5 in the UK, where our loss function has 2,664 elements.¹ While we have not yet created separate weights for each UK region, we include region-specific targets (like the CPS, the UK household survey has region identifiers).

In the US, we have completed step 1, and also made progress importing the Survey of Consumer Finances and Consumer Expenditure Survey to our data format.

Why our approach will work#

We’ve grounded our algorithm in theory and empirics to maximize accuracy.

My 2018 paper,

This result aligns with the theory underpinning each method. By finding the nearest donor record, matching routines are almost built to overfit, while random forests are architected to avoid overfitting.² Overfitting matters because data fusion is not a linking problem, it is an out-of-sample prediction problem: none of the records in the PUF are in the CPS, and vice versa. We aim to predict the conditional distribution of variables using companion datasets, reflecting the uncertainty in these predictions.

Our reweighting routine also carries theoretical advantages over the state of the art. Institutions like the Census Bureau assign initial weights using a small number of covariates, without intending to correct for sampling bias in outcomes like food assistance participation. Analysts sometimes adjust these weights to consider more outcomes using nonlinear programming, which runs until all constraints are satisfied (e.g., each income category is within 5% of the true values). Gradient descent improves upon nonlinear programming by continuing the search: rather than merely looking for an acceptable solution, it finds an optimum after hundreds of searches (“epochs”). And because gradient descent powers deep learning models, computer scientists have built tools to make it run smoothly and quickly.

Since reweighting is also a prediction problem, we evaluate our method on holdout sets of metrics to avoid overfitting. My colleague Nikhil Woodruff has shown that our approach here

Our UK documentation includes

The CPS already produces useful projections for some policy reforms, such as national tax programs that affect the bulk of the income distribution. Our experience in the UK suggests that our data enhancement procedure can make it even more useful; we expect to cut errors by 90% for assessing more targeted policies, and also to be able to model reforms we don’t currently support, like the

By enhancing the CPS with IRS tax records and reweighting it to minimize deviations from administrative aggregates, we can significantly improve the accuracy of policy simulations and contribute to a more evidence-based policymaking process. We look forward to bringing these enhancements to the US and making our enhanced dataset available as an open resource for other policy research.

¹ The UK equivalents of the CPS and IRS tax records are the Family Resources Survey and Survey of Personal Incomes, respectively. Our code for enhancing UK microdata is in

² While we expect that deep neural networks could outperform random forests with tuning, we’ve adopted random forests for their simplicity and high baseline performance.

max ghenis

PolicyEngine's Co-founder and CEO

Subscribe to PolicyEngine

Get the latests posts delivered right to your inbox.

© 2025 PolicyEngine. All rights reserved.