How PolicyEngine estimates the effects of UK carbon taxes

By fusing datasets with machine learning, we empower anyone to integrate custom carbon taxes with other tax and benefit reforms.

Contents

Breaking down the carbon tax

Estimating households’ carbon consumption

Estimating households’ exposure to carbon taxes through shareholding

Overall results

Household impacts

A carbon tax is a fixed price paid by corporations for every tonne of carbon dioxide emitted as part of their production process. Typically, it’s levied at the fossil fuel source (oil well, coal mine, gas site, etc.), or at the border for high-carbon imports. This tax has been

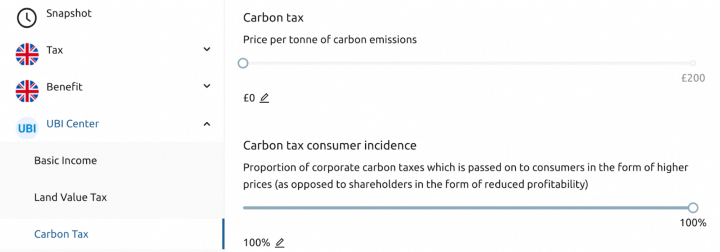

PolicyEngine allows users to simulate policies implementing carbon taxes in the UK (see the UBI Center policy menu), and adjust the assumptions on their incidence. In this post, we’ll go through how we estimate the effects of the tax.

Where to find carbon taxes in the PolicyEngine UK policy screen.

Breaking down the carbon tax#

PolicyEngine is a *static *model; that is, we assume that policy reforms do not change behaviour. Still, we allocate the burden of taxes to households, including taxes levied on corporations like a carbon tax.

Static models can allocate production taxes in three ways:

-

To consumers in the form of higher prices

-

To shareholders in the form of lower investment values

-

To employees in the form of lower wages

PolicyEngine currently models burdens on consumers and shareholders only, not yet employees. Our carbon tax model also allows users to change the share of the tax borne by consumers versus shareholders (the default value is 100% consumer burden).

The following two sections describe how we allocate the consumer and shareholder portions of the carbon tax to households, respectively.

Estimating households’ carbon consumption#

We use several data sources to estimate households’ carbon emissions:

-

The Family Resources Survey (FRS)

-

The Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS)

-

Carbon footprint estimates from the Office of National Statistics (ONS)

The FRS forms the foundation of PolicyEngine because of its detailed data on income, benefits, and demographics. However, it doesn’t contain information on household spending by consumption category; for that, we use the LCFS (which also has less detailed data on income and demographics). Exploiting the common variables across data sets, we build a model from the LCFS that predicts spending given income, and apply that to the FRS households. Specifically, we use our

We apply a similar method with the ONS carbon footprint statistics. This data reports the total carbon emissions associated with each category of spending (the same categorisation as the LCFS uses). We also know the total spending associated with each category from the Living Costs and Food Survey (and now in the FRS, too). This enables us to estimate the carbon intensity of each category: the carbon emissions associated with each pound spent. We can then multiply this intensity directly by the amount spent on each category to find the estimated carbon emissions for a given household.

Carbon emissions intensity by spending category.

This full process then provides estimated carbon emissions for each household in the FRS.

Estimating households’ exposure to carbon taxes through shareholding#

Since we don’t model the ability of firms to lower wages, the other half of the static carbon tax burden is households’ exposure through ownership of firms that would pay it. We assume that shareholders of companies will pay the carbon price, proportionally to their equity. Since we don’t have data on the types of companies that households invest in (only total equity holdings), we assume that their exposure is proportional to their total equity in all firms.

We calculate this at the household level, to integrate it with the rest of our model (and because all taxes are ultimately incident on households). In a similar manner to how we imputed consumption from the LCFS, we impute corporate wealth from the Wealth and Assets Survey for each FRS household. We then calculate the total shareholder-borne carbon tax, and distribute this proportionately to households with corporate wealth: this part of the tax is then no longer paid by consumers, only shareholders.

Overall results#

As

Change to net income by equivalised disposable income decile for a £100 carbon tax, assuming 100% consumer incidence.

Increasing the proportion of the carbon tax borne by shareholders makes the carbon tax slightly more regressive from an income perspective, though less regressive from a wealth perspective. Many policy proposals include revenue recycling options, such as a per-capita dividend, to address regressivity.

Household impacts#

PolicyEngine’s household page allows users to enter their spending on various consumption categories to estimate their burden from a carbon tax. For example, since the

Where to enter spending by consumption category in the PolicyEngine household screen to estimate carbon tax burdens.

By fusing multiple data sources, PolicyEngine UK for the first time empowers anyone to design custom carbon taxes in conjunction with other tax and benefit reforms, and then to compute the population-wide and personalised impacts. If you have any questions or feedback about our model, please

Thanks to Inés Fernández Barhumi and Reema Mohanty for their research assistance on our carbon tax model.

nikhil woodruff

PolicyEngine's Co-founder and CTO

Subscribe to PolicyEngine

Get the latests posts delivered right to your inbox.

PolicyEngine is a registered charity with the Charity Commission of England and Wales (no. 1210532) and as a private company limited by guarantee with Companies House (no. 15023806).

© 2025 PolicyEngine. All rights reserved.